The Demystification Of Music

by Mark Almond

Amazing things happen when we achieve a functional understanding of the nature of “harmony” in music. This can happen much faster than what the vast majority of music lovers can possibly imagine. Harmony, at its very core, is based on just a “few simple relationships” that can be explained and demonstrated in a matter of minutes. The secret to approaching this fascinating subject is to gradually build out from the center “while producing a wide variety of impressive musical sounds.” The piano keyboard is perhaps the best medium since it allows us to see a perfect “sequential” picture of all of the possible tones used in producing music.

Amazing things happen when we achieve a functional understanding of the nature of “harmony” in music. This can happen much faster than what the vast majority of music lovers can possibly imagine. Harmony, at its very core, is based on just a “few simple relationships” that can be explained and demonstrated in a matter of minutes. The secret to approaching this fascinating subject is to gradually build out from the center “while producing a wide variety of impressive musical sounds.” The piano keyboard is perhaps the best medium since it allows us to see a perfect “sequential” picture of all of the possible tones used in producing music.

Jean Philippe Rameau

The place to start, above all others, is to pay very close attention to the greatest single discovery in the history of music education. The composer Jean Philippe Rameau shocked the world in the early 1700s when he claimed that he could analyze and describe the main reason that music sounds like music. He claimed that all music has “only two primary building blocks.” This usually leads most people, especially those with music backgrounds, to jump to the conclusion that Rameau’s analysis is much too simplistic and therefore absurd. If this knee jerk reaction to his claim is correct, why then do you suppose Rameau was so often given the name “father of modern harmony” in countless history books and text books? Why was he, for generations, also called the “Newton of music” throughout Europe and eventually all over the world? This is confirmed even in Wikipedia. Search “Rameau” and look for the heading “Theoretical Works” toward the bottom of the entry.

Keep in mind that debating the theoretical in regard to Rameau’s discoveries becomes suddenly less relevant when you introduce examples of the music that can be instantly produced based on his analysis. No one, no matter how extensive their musical training, can disprove or discredit the insights of Rameau once the music itself is demonstrated. As it turns out, Rameau’s claim that there are only two primary building blocks at the base of all music is true to a degree that is truly astounding.

The whole point of this article is to list clearly what is at stake, no matter how controversial these points may appear to be initially. The sad reality is that so many people of all ages are wasting so much time and energy solely because their understanding of the basic elements of music is deficient, often to the point of being nonexistent. Here is a partial list of what is really at stake:

-

Our ability to successfully teach a much higher percentage of three and four year olds to learn to love playing the piano, and continue playing the piano and other instruments for the rest of their lives;

Our ability to successfully teach a much higher percentage of three and four year olds to learn to love playing the piano, and continue playing the piano and other instruments for the rest of their lives;- The skill to play music with the various kinds of rhythm that powerfully communicate musicality;

- The opportunity to learn to read music notation more efficiently while at the same time acquiring that elusive quality of fluency;

- The ability to memorize music with drastically less effort;

- The guarantee that all pianists will have a complete foundation leading to the ability to both improvise and compose;

- The wisdom to understand the nature of the most productive elements of practicing;

- The talent to master what are often considered to be the impossible pieces.

On a personal note, based on the limited understanding of harmony that I had during my college years, I could have practiced the Liszt B minor Sonata literally for my entire lifetime without ever being able to master it. If you cannot see exactly how Liszt creatively manipulates a few simple patterns, learning a masterwork like this one would take well over thirty times longer if you could ever learn it at all. Even if you somehow memorize the notes, that is miles from being able to play the music expressively. On the other hand, if you can see through the complexity to the underlying design, few people will believe you when you tell them how long it took you to learn a thirty-five page monster with sixteen key signature changes.

There are two main reasons Rameau’s tremendous insight into the design of music did not make a much larger impact in the world of music education. First of all, he buried the very core of his breakthrough with tons of trivial material, much of which music scholars of today cannot decipher. Most important, as we try to dissect his partial failure to fully communicate his discovery, Rameau did not take the time to lay out a step by step unfolding of his insights that beginning and intermediate students could understand. This failure is extremely unfortunate since Rameau’s analysis opens up a pathway that enables any and every piano student to immediately play emotionally satisfying music once they see how to apply basic rhythms to these “units of harmony.” Ironically, even the professionals who initially disagree with the Rameau analysis will usually agree with it by the end of their life as they learn by experience to see more of the underlying structures—the simple patterns which have been staring them in the face for decades. Unfortunately, their late in life breakthroughs do not usually help the people around them.

There are two main reasons Rameau’s tremendous insight into the design of music did not make a much larger impact in the world of music education. First of all, he buried the very core of his breakthrough with tons of trivial material, much of which music scholars of today cannot decipher. Most important, as we try to dissect his partial failure to fully communicate his discovery, Rameau did not take the time to lay out a step by step unfolding of his insights that beginning and intermediate students could understand. This failure is extremely unfortunate since Rameau’s analysis opens up a pathway that enables any and every piano student to immediately play emotionally satisfying music once they see how to apply basic rhythms to these “units of harmony.” Ironically, even the professionals who initially disagree with the Rameau analysis will usually agree with it by the end of their life as they learn by experience to see more of the underlying structures—the simple patterns which have been staring them in the face for decades. Unfortunately, their late in life breakthroughs do not usually help the people around them.

From a historical point of view, even the widespread influence that Rameau did have on musicians was nearly destroyed by a popular trend that began around the beginning of the 20th century. It became fashionable worldwide to question the validity and value of those “old rules of harmony.” Traditional harmony was suddenly viewed as “restrictive” and believed to limit our creative freedoms. The large volume of music written during this period is usually described as “atonal.” What this global group of composers ended up with was music with clever melodies and clever rhythms, but devoid of harmonies that could reach listeners on an emotional level. It turns out that the composers of previous generations knew a little bit more than they were given credit for. The “new music” created by this turn of the century trend, which was really nothing other than generational arrogance, is all but dead and gone today. You might hear some of this atonal music in a stuffy classical concert – played as a curiosity, but this kind of music was never even close to being popular with the public.

The extensive damage perpetuated by this atonal trend was not only destructive to the music being composed at the time, but inevitably, horrific damage was also done to music education. An open attack on the underlying principles of harmony turned out to be a devastating attack on all music students. One result, still wreaking havoc today, is the widespread tendency to reduce piano instruction down to the level of teaching, note reading only. All method books claim to teach chords, scales, and harmony, but they simply do not break things down to the point where they make sense. Students end up unable to see or utilize the critically important and all pervasive building blocks that allow us to truly understand music.

Since it is life changing for those willing to start down the pathway of exploring the practical side of harmony, it is well worth a quick trip to a piano to verify the details of Rameau’s analysis. This is a little easier to demonstrate in a live lesson, or in a DVD lesson, because of the visual aid of seeing things on the piano keyboard, but a verbal description will also work great if you should try playing these ideas on your own.

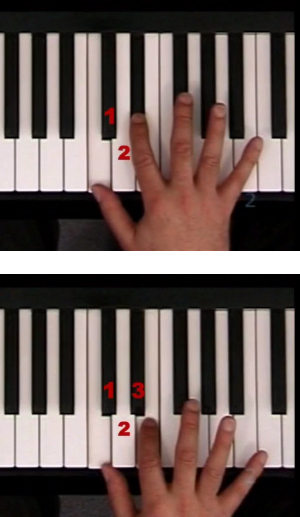

The first building block is the distance, or interval, where there are two keys between the two keys that you are playing. If you are careful to count both the white keys and the black keys in this process, you will find this very easy to do. This first one creates a serious, sad, dark mood even when played by itself. Try playing these two keys repeatedly while using the sustain pedal in order to bring out the mood.

The first building block is the distance, or interval, where there are two keys between the two keys that you are playing. If you are careful to count both the white keys and the black keys in this process, you will find this very easy to do. This first one creates a serious, sad, dark mood even when played by itself. Try playing these two keys repeatedly while using the sustain pedal in order to bring out the mood.

The second building block is the distance where there are three keys between the two keys you are playing. This one creates a bright happy sound, especially if you play it repeatedly. These two building blocks are so easy to understand and play that you may grossly underestimate how far these structures will take you once you learn how to combine them, or stack them. Even non-musicians hear guitar players and pianists talk about major chords, minor chords, diminished chords, and augmented chords. You may find it hard to believe, but there is an even longer list than just these four, that are all built by using only the two building blocks just described. When you learn to “stack” these two basic elements on top of each other in various combinations, a whole world of music opens up.

Once you can build chords, the next step is to play groups of chords in some of the sequences that can be found in songs. This is called a chord progression. An entire song may have only four or five chords that repeat over and over again in a certain sequence. As an additional step, adding a simple rhythm to a chord progression is shocking in terms of the musical sounds that can be produced. Then try adding matching bass notes, played in the lower part of the keyboard, which will add a much fuller sound. Another surprise is soon to come when you learn that all of the advanced professional sounding chords are also very simple in structure and easy to learn if you simply analyze how they are built.

There is one barrier that prevents many people from succeeding with a practical chord approach. It is very important to learn the names of the 7 white keys on the piano keyboard (A / G) so that all 7 of them can be located without hesitation. If this is done carefully and at the right pace, it is not much harder than learning the names of seven people you have just met. This simple skill of knowing the key names will remove one of the main causes of frustration while you are learning to be creative in your exploration of chord progressions.

You may be wondering about learning to play the melodies of particular songs. The great news is that all melodies are closely related to the chords that support them. Pianists who are skilled in understanding and using chords can quickly learn melodies because they learn to see how the melody is interacting with the various chords as the song progresses. All melodies are “free” in structure and totally unpredictable in relation to their movement. The melody of a song “dances around each chord” often using tones that are in the chord, but nearly half of the time, on average, the melody employs tones that clash with the chord. This is why melodies are more complex, harder to analyze, and practically infinite in number. Chords are very limited in number, consistent in structure for all kinds of music, and can be understood by everyone. Chords form the basis for all melodic activity. Increased skill in recognizing chords translates directly into the most efficient means of learning new melodies. If you limit yourself to memorizing individual melodies, one after another, this will have little strategic value and guide you straight into a brick wall in relation to your overall development.

Music has structure. Music is organized in a way that is understandable. On the surface it seems like music is so complex that no one could possibly understand it. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Music, all music, is based on only two primary building blocks. Understanding how this unfolds is the white hot center of music education. This analysis can be demonstrated to the point where no one can successfully disprove it.

In addition, there are other layers of organization beyond what has been discussed in this article, all of which are of great encouragement to aspiring pianists. All of these analytical insights can be utilized alongside all of the traditional instructional materials. For example, a practical knowledge of chords throws a tremendous amount of light on the purpose and value of the various kinds of scales. Scales also throw light on chords. Working toward and achieving a fuller understanding of the true nature of music opens up endless possibilities to everyone with a deep desire to learn.